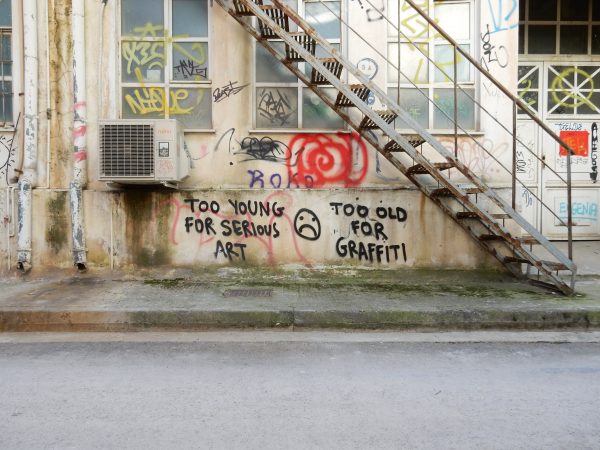

My first encounter with Sotiris Fokeas, aka Soteur, took place during a photo stroll around the Athens School of Fine Arts on a sunny January day—once in person and then again through his work. First, I ran into Sotiris, at the time an MFA student at the university, leisurely working on a colorful mural on one of the many walls on campus, striking up a brief conversation. A bit later, having returned to my solitary pursuit of photo documentation, I came upon the slogan “Too young for serious art, too old for graffiti,” a thoroughly Athenian conundrum, perfectly placed between a fire escape and an AC unit on the back of a university building. Only later that day, with some help from Instagram, did I connect the two, getting my first glimpse at the slogan-writing and meme-generating street artist, fine arts student, and online persona that is Soteur.

Several months, conversations, and one Athenian COVID lockdown later, in the heat of August, Sotiris and I reconvened over coffee to speak about his work, his politics, his love for humorous slogans, and how he stayed busy and painting during the pandemic (hint: this story involves a rooftop and a sun stroke). Make sure to follow his work on Instagram and Facebook—and maybe consider buying this working artist a meal sometime through his webshop, he just earned his MFA after all!

*

Let’s start with your beginning. You started doing street art in graffiti, as you said in other interviews, at 18, when you first joined the Athens School of Fine Arts…

No, younger—14, 15, teenager revolution and stuff! But I got more into it when I got into the university. I did a lot of graffiti, lettering, and stuff like that with my crew, all this teenage stuff, and at some point I decided that I want to know how to draw better. I also always wanted to become an artist because I thought it was super cool. So I got into the university and started doing more characters, graffiti characters, portraits and stuff. So this is how I got into it.

I always loved graffiti because it’s a really cool way to hang out with my friends. Indeed, that was the whole thing, because I started art school, and I always loved painting and doing exhibitions and stuff like that, but when we go along with my friends, not everyone was a professional artist or wanted to be an artist, it was just really fun—it still is. Instead of going for a coffee, we go out for painting and drank the coffee or the beer there, at legal graffiti walls. I don’t do a lot of illegal anymore, I only do illegal stuff when I feel super super safe, or when I want to do something that’s really small and accurate. I mainly don’t do tags, but συνθήματα [slogans], writings on walls. Most people don’t even know it’s mine.

So yeah, I guess this is the beginning. Because after a point I decided that since graffiti is so popular in Greece it’s an easy way to promote my work and my art to the general public, people that are not art friends or art lovers. I guess more people can relate to graffiti than to an exhibition, and more people will see it. So I kind of use it as a tool to promote my whole world, if that makes sense.

How does what you do within the context of your fine art degree relate to the work that you do on the street.

I see it as a tool. Graffiti and the stuff I do online, on social media, Instagram mostly now, I see them like this: tools for me to communicate my work to even more people. Like, for example, I find that if the point of my work is to communicate a message, it doesn’t make sense for me to do it with oil and canvas, a really expensive niche exhibition, stuff like that. It’s easier to do it online and in the street. So it’s a really useful tool that also happens to be really fun, and it also has a little bit of nostalgia in it. When we paint all together it’s like, we’ve been doing this, hanging out and painting, since we were 15 years old. And many times the same group of people, which is very very cute and fun and nostalgic.

Let’s move on to the question of style. As you said, what you do now is mostly slogans—you often also call them quotes—which are often very ironic or playful. They poke fun at things, they don’t take themselves very seriously. And you often attribute this to your time working in internet marketing, and the kind of internet meme culture and the humor of that, but it also makes me often think of the humor of political slogans and protest in Greece as well. Does that plays a role for you as well?

First of all, I love them. There’s a really funny story that I had forgotten about and remembered recently about the first book I bought when I was really young. My mother had this thing, when we went to a book store she told me, “When it’s about books, you will not care about money, you can have whatever you want. Just tell me which book you want and I will buy it for you.” Because she always loved books. And the first book I chose for myself was a book with slogans from the street.

Really?

Yeah, it was like a really old weird book. I don’t remember what it was called, but I have to visit my mother’s house and find it.

How old were you?

About 8 years old.

Oh wow, that’s some real foreshadowing!

And it was like the first book I chose…and the second one was a graffiti book! The first book I chose was a book with funny statements on the streets of Athens, like slogans and quotes in public toilets. And I remember this: there was a picture in a public toilet, where the wall was broken and someone wrote, with an arrow pointing at the broken part, “Bruce Lee was here.” This kind of stuff, stupid things. And I loved this book, I found it so funny. I still do. So I guess I’ve been carrying this subconsciously my whole life.

Slogans, and quotes and words in art are also a really useful tool for humorous artists to make their work even more fun and funny. A funny drawing might be considered just a bad drawing, but if you write a stupid quote under it… My favorite artist is David Shrigley, British guy, who is fucking hilarious, and I remember going to his exhibition, a solo show in London, and everyone was laughing. Like, instead of the typical glass-of-wine art viewer face, you met people at the hallway and you were laughing with each other. And I was like: this is what I want to do! I want people to come to my exhibitions and have fun and laugh at each other.

So yeah, quotes are a really useful tool. Outside of the academic and the art world it’s a way to be more precise and to communicate messages in a more direct way. And for me, being inside the art world and inside academia, where everything is more serious, doing this kind of stuff is kind of an artistic statement. Because, like, okay, you decided to do a painting, oil on canvas, and exhibit it, and in the same room I decided to exhibit a quote, that was done with a pencil in one second. I think it’s a really strong statement.

Most, if not all of your quotes are in English. Can you talk a bit about why that is, why you made that decision and who you thereby conceive of as your audience?

I don’t want to talk only to the people in Greece. I prefer to communicate messages to everyone. I don’t know, I guess it’s not that important to me. English is a language that almost everyone in Greece speaks, and there’s no point on writing stuff in Greek for me. I do write some stuff in Greek, but I use Greek only when it’s something that it should be in Greek, that only makes sense in Greek. Also, our generation is not located in Athens. Most of my childhood friends live abroad, so their world or their friends are not Greek. So it makes way more sense, but it’s really not that important. I just chose the language if it fits, I guess.

Do you consider your work political? Because you make a lot of statements about how it really isn’t, but of course you do speak to very real issues, especially the precarity of artists. And recently you’ve also made more explicitly political statement with regard to police brutality. So, what are your politics in the context of your work, and how has that maybe also changed in the last couple of months.

First of all, I think everything is political, everything you do or produce is political. I consider my work to be political from day 0. The thing is, I don’t know if this comes through, because it has many layers, and not in the fancy way. For example my Instagram stuff started as kind of a joke, a character, a performance or something like that: a funny guy who does cute colors and makes a living out of art, which is a political statement if you see the whole picture. But I don’t know if this comes through for someone who doesn’t know all aspects of my work. I’ve been kind of split, because my work, the work people see on the internet, in comparison to the work people see if they visit an exhibition is kind of different. So yes, my work is 100% political, and I could never consider not doing something that has a political aspect, but I don’t know if I do it well.

I have this fear that people think I’m just a fun pop art guy, who only does funky colors. I don’t know. This is kind of the subject of my MFA thesis: How can someone adopt the role of a clown to speak the truth, like the whole theory of the wise fool. Adopting a more silly personality, and a more fun personality, and a more laid back personality, in a society where everything is crap and where everyone tries to speak seriously, might be more wise in many many ways than actually trying to speak seriously.

Yeah, I think that’s also why a lot of the traditions of political slogan writing rely on humor as a lens for making other statements, not just in Athens, but lots of other places and contexts: the Occupy Gezi uprising in Istanbul, the current BLM stuff, there’s a lot of humor about the tear gas. You have to kind of take up the humor to alleviate some of the seriousness, because otherwise it becomes too heavy.

Exactly! And it’s also the same thing I was trying to talk about earlier: it gets more people. Unfortunately, art, especially in Greece, has this image of being something that’s kind of for the high society, for the more cultured, I don’t know, educate people, the rich, the pretentious folks. So filtering everything through this, through humorous voice, makes more people interested in it and gets the message to more receivers. I want to communicate my message to as many people as possible. It’s weird to say that I communicate my super special truth only to the selected few. It defeats the cause.

I want to move from here into the question of crisis, which is, of course, always kind of implicit when we talk about political issues in Greece. For as much as people tell us the crisis is over, it’s still a reality and also always looms large in the field of street art and graffiti because crisis street art and graffiti became such a thing for a few years. How do you relate to this broader context of crisis as both a lived reality and this symbolic thing weighing down on Athens?

I’ll tell you what. Since me and my friends, we’ve been here and we lived through the whole thing, I do not know if it has any actual impact in our work. What I get the most is this idea of the struggling artist, the Greek street artists. Whenever I’m abroad for an exhibition or something, I kind of get the feeling that people treat us, Greek artists, like this mysterious creatures that produce art on the crisis. And we are, on the other side, like: “Come on we would do this anyway, nothing would change!” So I don’t feel this affected by the crisis in a creative way, because it’s the condition we live in. If it wasn’t for the crisis is would be something else. The only thing that really affects me is when a lot of things happen back to back. This period is, honestly, crazy. It’s the COVID-19, Black Lives Matter, this, that. Every week there’s something new. But the crisis, I don’t think, has so much impact. Because we have been in it since day 0. I started my career in the crisis. And most of the people I know who are now 30 years old, most of us started doing what we do in the crisis, so I guess we’re kind of used to it.

The only weird thing about Greeks and the crisis is our parents’ generation. Those are the guys that freaked out and got shocked, because they lived in a world that was completely different. But we do not know much else.

And it’s also funny because if you are…I know it sounds weird, but these are honestly our best years, 20 to 30, it’s a great decade. And all the things we’ve done and I’ve done, and the best things I’ve done are in this decade. So for me it’s a good decade. I don’t think “Ah, it used to be better.” I was 10 years old, I don’t remember it. I think the crisis is more something that people outside of our community like to talk about when they point at us, but we don’t talk about the crisis this much.

You’ve already talked about this a little bit, but I would love to hear a little more about how you have been impacted by what’s happening now, the COVID pandemic, both as an art student and as a street artist. And I’d love to hear a little more about this rooftop painting action you did, because that was really fun to see. But then I’d also like to hear about this thing, on your website shop you have the “support a struggling artist,” where people can buy you a meal for 10€, buy you shoes for 50€ and buy you rent for 200€, and it’s the only thing in your shop right now. You also refer to yourself as an art worker, and of course there’s been a movement for supporting art workers in Greece during COVID, so I’d love to hear about these various strands of being affected and responding to the moment.

Well, the thing is, it’s a bit of a coincidence, I guess, because I had always been treating my e-shop like that. I always found it funny to have an empty shop. Because I don’t produce much stuff to sell—pieces, prints, t-shirts—I’m usually able to sell them through Instagram in a day, so I don’t have stock. So my e-shop cannot have stock pieces for people to buy. So I always find it funny, okay, if you really want to support an art worker, you can buy me a meal. And then the whole Support Art Workers movement happened in Greece, and people started visiting my shop. And everyone thought that I closed all my products and only left the support art worker thing. But I always had it like that. And people found it really cool, they were like “Ah, it’s a really cool statement!” But that was always the deal.

But yeah, the situation with COVID and everything around it…Most artists, we work in one of two ways. One way is reacting to stuff that happens, and the other is making them part of you and having them change you. I do not believe that the things that have been happening now have changed me yet, or I’m not used to them yet, so that I can talk with certainty about how I relate. So what I do now, I guess, is kind of collect data and information on what’s going on, and react in kind of a childish way. Even though I want to process stuff more sometimes, I cannot keep my mouth shut most of the time. And I honestly love having this freedom of: “Oh I thought of this and I’ll say it, because I’m an artist.” I find it very very funny. But I’m still processing information and collecting data and trying to figure out what the fuck is going on with everything.

And yeah, the rooftop thing happened during lockdown. I didn’t have access to my studio, because it’s kind of far away from where I live. And I wanted to paint and I had to prepare some commissions and stuff like that. But I was not in the mood for doing work, so I decided to do this thing that I was talking about, hanging out with my friends and doing graffiti, and I thought I’m going to do this by myself, I’m going to have my morning coffee on the roof and I will do my graffiti on the cellophane. And it was very cool because it was an exercise, and as an exercise it was very good because I didn’t have to keep the pieces afterwards, they got destroyed immediately. You keep the picture, it’s the same thing as street art. It was really fun and I really enjoyed myself, actually I got so happy with it that I stayed on the roof for two days and got ηλίαση…

A sun stroke?

Yes.

Oh shit!

So I was two days on the roof and then I had fever for another two days and I thought I had COVID.

[laughter]

Like, I have the fever, I am dying! I have the cough. I’ve been quarantining for two months and I got COVID alone.

On your roof…

On my roof.

It’s a great idea though, I have rarely seen cellophane used like this anywhere else, the only instance I remember is a spot in Berlin, where it was used as a banner, strung up between two trees.

Yeah they do it a lot! And I had forgotten about it, and I remembered it in my sleep, during the lockdown. I was like “I want to paint, I want to paint” and then when I was sleeping, which is when I get all my good ideas, I remembered this: a festival in a forest where people were wrapping trees and doing graffiti and I was like “This is what I want to do!” And I ordered some cellophane, and it was very fun. It was nice because I didn’t like the lockdown at all. I hated being in my house and not working and not being able to go to my studio. These were the best days in the lockdown for me. Painting like nothing is wrong, posting things on Instagram “I’m having fun on the roof doing graffiti.” It was nice.

We already talked a little about the current state of the street art and graffiti scene in Greece, which is marked by a strange coincidence of graffiti removal being very promoted by the mayor’s office and then also street art, commissioned street art, being embraced very heavily by the city as a motor of creative revitalization. Where do you see the Athens street art and graffiti scene moving?

I think the first important thing is the young artists, because graffiti artists have the best energy, creative-wise, production-wise. The energy of the graffiti artists is insane. There are 19-year-old kids who do 3000 pieces a year. They paint like crazy, they do 5 pieces a day, insane energy. And this is not the energy you see in a university. Other artists in Greece do not work like that. And I really appreciate the energy and the way that graffiti artists work. And I don’t think that this energy can be stopped by the anti-graffiti movement. As I told you before, it only gets them more passionate and more angry and more energetic. And I think that, in a way, the commissioned stuff, kind of helps with that thing. Because when a young artist, like 18 years old, sees that you can make a living out of it, it is a good thing—if I want to see the good aspect of it. Because the bad aspect, the whole gentrification, and rents going up, and Airbnb, it is bad, it is bad for the city. In a way it’s better because it’s safer to walk outside, but it’s very bad for the city. But I honestly don’t think this energy will ever stop. I remember the first time I saw anti-graffiti paint on a wall, artists were there with hammers and nails breaking the wall down and trying to paint like that. This is how we were. When I was 16, 17, 18 years old, the only thing that I loved doing was painting, no one could stop that.

—

This interview was conducted in person on August 11, 2020.

Questions and editing by Julia Tulke.