Cleo43, one of the most prolific female street artists active on the walls of Athens, is best known for her colorful and elaborate masks but got her start writing graffiti as a young teenager. She kindly sat down with me last summer to share some insights about her artistic biography, her aesthetic politics, and how issues of gender and feminism inform her creative practice and relationship to the city in crisis. You can follow her work on Facebook.

So maybe to begin you could tell me a little bit about how you started out doing street art, doing creative work in general.

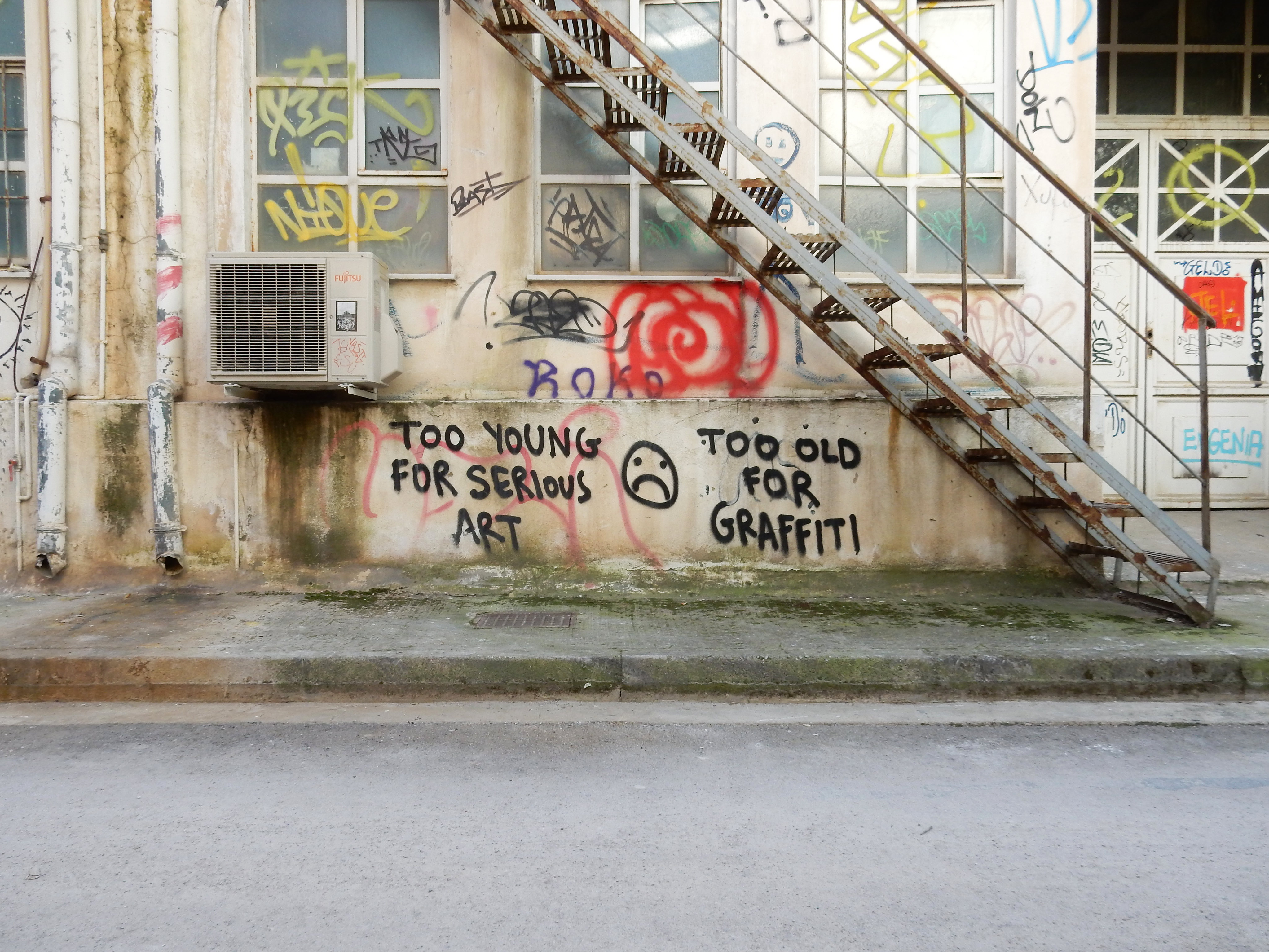

I was really young, about 12 or 13 years old. I was quite a boy back then. My father raised me and my sister and we were the kind of girls that wanted to do ballet but he said: No, you do Karate! It was fun because we were strong from a very young age. Most of my friends were boys and unfortunately—or fortunately—most of them were graffiti writers. So we would go out together.

So that’s how it began. And I loved doing that for many years, small stuff, tagging and symbols. More for me, not something like a big portrait or a piece of street art, trying to think before you do what you do, choosing the colors, choosing the spot, the weather, friends to check out for you.

And then a few years ago I finished college, first in sociology, then fine arts school. So I started painting a lot and working in art direction, making masks and props for music bands and commercials and TV, and then I started drawing and putting my work on the canvases, on the streets. That’s how it began, about four years ago. Before that I was using my tag name, but a different one.

So you didn’t go as Cleo43, what was your tag?

Saman.

So when did you chose to go as Cleo43 and what does it mean to you?

Cleo is my one grandmother’s name, and 1943 was the birth year of another one. It’s like putting my two grandmas together almost. The reason I chose that is that they are great role models, female role models, for me. I have a tattoo of her, not her face but an owl that symbolizes her.

You’ve already hinted at issues of feminism, can you tell me a little bit about whether you consider your work a kind of feminist intervention, and where you locate the politics of your practice? I’m thinking for instance about the positionality of being a woman in public space, or being a graffiti artist in a largely male-dominated subculture. How does that inform your work and creative practice?

A lot, it’s my nature. I love to hang around with my friends that usually are boys. I also like to do stuff that usually women don’t. But it’s difficult, and it’s even more difficult between women. You can see a lot of competition between us, which is a little sad. I believe in unity, not just between women but in society.

I try to read a lot about feminism. The cool thing is to see is that there are a lot of women that feel the same way and that also want to change something. The sad thing is that most men do not and they’re a little stuck in the past. So it’s very important to me. And I also try to communicate that through my art. I try to influence in a good way any woman or man or any human being, I’m trying to be good so that I can influence them in a good manner.

It was great being a part of Femme Fierce last year.

Cleo43 in one of her signature masks in front of her mural for the 2015 Femme Fierce Leake Street All Girl Takeover in London

Tell me a little about that, how many artists were there?

It’s great, you see about 100 women and also 2 men dressed up like women with high heels and lipstick—and it’s cool. So you get a lot of good vibes. If you’ve been slapped around all the time for what you do and for not being a boy— and you can not possibly learn graffiti if you’re not—you get confidence and good energy, it was like recharging my batteries. Because you see that you’re not alone.

So having visited Athens multiple times since 2013 I’ve gotten the impression that since 2015/16 there has been a lot more explicitly feminist graffiti and street art in the streets. I see a lot of feminist slogans, against rape culture, or about body positivity, I saw some queer graffiti, and I didn’t see any of this back in 2013. Do get that sense, too, that feminism is becoming more of an issue in public space?

Yes. Greece still has a lot of work to do but since 2013, with everything going on in the political realm, you can see that people are trying to go more deep. So there’s no money left, no American dream left, so you have to read, you have to watch out for your people, see what is going on and start to think about other people, about yourself and your ideals. Materialism ended. The good thing about all this—and I’m an optimist by the way—is that people started to think about ideas and ideals.

So feminism is one of those things that I also see as evolving, because women now have to feel more strong, because their lives are changing. When you fall and you get hurt you don’t have anything to lose. So if you feel like you want to express your sexuality or you want to express your art or if you feel like you want to do art on the streets—which is a very important medium, because everybody sees it. It figures: people are feeling more free to do what they want. With a lot of fear of course, and poverty.

So if you go out in the street, do you have a specific process? Do you go out with a place in mind for a specific artwork or do you see the space and then decide what you want to do with it?

I first see the spot, I’m inspired from the spot, and then I chose my material and then the right time, the right weather. Police is more like . . . this is the good thing about being a girl, they will come through and see you painting and they will say aww, that’s just a little girl painting. So they go away.

When do you usually go out?

I would never go out a place like this in the evening, when it’s full of people drinking alcohol, partying. I would do it at six in the morning or seven, when you can see pigeons. The last piece I did was about two weeks ago in Kifissia in an abandoned house full of graffiti. It’s a bit dangerous sometimes, because you have to climb, you have to be careful with needles from drugs. Also there are floors that are almost fading out, and you might fade out with that. But it has this adrenaline. I don’t know how that happens but every abandoned building has some really cool spots to paint.

You seem to collaborate with quite a few people, tell me about that.

I love to collaborate with people! I feel the same thing about art, it’s like a team work. Of course there are things that you want to do by yourself, that work for you, but from time to time it’s more fun doing stuff with others. I am happy even to do the background for a tag.

Tell me about the role of masks in your artwork?

The first time I did a mask for the theatre in Empros for a Greek newspaper Ethnos. They did an interview and really wanted a photo and I didn’t yet have a piece that was good or photographed. Of course the cool thing about doing things outside is that they fade away. And at that point I think that most of what I did was not very organized. So this was the first time I did a two-dimensional mask and I liked it more than the other things. My upcoming solo exhibition is going to be about the masks also. There are going to be the masks in frames and a photographic project with some symbols drawn on bodies.

So since you bring up news media, what are your thoughts on the media frenzy about Greek street art in the crisis?

It has to do with your beliefs. I don’t believe in politics. For me seeing all of the disgusting things going on, seeing that everyone is the same and corruption is everywhere, I began to make a world of your own. And my world doesn’t involve politics. When the big mural went up at the Polytechnic university in Athens the media wanted to blend it with politics. At the time a lot of media outlets tried to contact me and other street artists, graffiti artists. But didn’t give any interviews then. I try to avoid interviews for television, and I have a good way to do that: I tell them that I don’t show my face but I wear masks and they usually say no. I think as an artist you can express your views and try to influence society in a good way, but I’m a bit against using politics or super-hyped themes in your art. It’s not my thing.

So if you say politics doesn’t play a part, how would you describe how the context of the crisis figures in your own work? Because it is there, as a material condition, a changed urban landscape, you cannot really separate it. So how do you negotiate the material effect of politics on your everyday life, and the city’s everyday life?

It’s in your art, it’s the same. If you look for example at the work of NAR he takes stuff from the streets. I also try to scramble stuff. Most of the fabric on the masks are found, or their stuff that I have. I am broke, everybody is broke right now, so I also work as a waitress to try to do my things, which I didn’t do this before the capital control crisis. I was in a better place. Not necessarily secure, but I don’t need a lot of stuff, I was good. Even regarding the theme of feminism, I felt more like expressing that, or trying to do something with that. So there are times that I’ve done work on the crisis but not so loud, not so on the spot. And I think you can do things to help.

How so?

Yeah, I think it’s more important to go see theatre than to go out to the bar to have a drink. Or to see art or go to the museum than being on coffee all the time, or out shopping. I don’t believe in politics but I think that in times of crisis, in dark times, art becomes more strong.

“The door is no open: wash with your colours the city’s eyes” Collaboration between Cleo43 and Black Flamingo in Psirri, June 2015

—

This interview was conducted in person on June 16, 2016.

Questions and editing by Julia Tulke.