When it comes to female graffiti writers in Athens, it is impossible to find someone as prolific and as sucessful as Nique, whose characters and pieces have adorned the walls of Athens since 2015. Having closely followed her rise to become one of the most recognized writers in the scene, I finally got to share a conversation with her this summer. I caught up with her during one of her busiest weeks of the year in the middle of four festivals and events all in the space of just a few days as she was painting a piece at Omonoia art space Romantso.

To begin, could you describe briefly how you came to be involved and graffiti, and talk about your experiences being a woman in this subculture?

Well, I started graffiti because of Hip Hop, as part of Hip Hop. At first, when I was about 14 or 15 I started with stencils and tags and all that stuff, and when I was about 17 I did my first piece with letters. So from then on, since 2016 or 2015, I haven’t stopped writing, that’s how it began. And actually I didn’t begin in Athens, I was living in a smaller city, it’s called Agrinio, where I went to school and I grew up. It was a little bit difficult to get connected with all of the people that were doing graffiti, or to get informed, because we didn’t even have fast internet back in those days. And it was really difficult even to find magazines.

As for being a woman in the scene: I think it has its pros and cons. Maybe people get to know you more easily because there aren’t many women, but I think it’s harder to persuade them that you are doing it [at the same level] as men do. But you know, bottom line, when you go out and you see a piece of art or graffiti, you don’t see who made it, it’s just a piece of art, and it doesn’t have any gender.

But of course there’s ways to put little markers of gender in the piece, right? Like colors or certain motifs.

Yeah, many people tell me that because of the colors they think that a girl has done some of my graffiti, because I use a lot of bright pink and bright colors—but so do men these days. They don’t have a problem with pink and those kind of colors, they are more open-minded these days.

Do you want people to recognize your artistry as something done by a woman?

No, that doesn’t matter to me. I just want it to be a good piece of art, not concerning the creator of the art.

Do you feel that the involvement of women in the graffiti scene is developing right now?

There are some more girls, but not that much I’d say. And they may do it for one or two years and then stop, they won’t do it constantly. But I think that will change, more women will begin to give it a shot at least, maybe not at graffiti but at street art, something that concludes art in different ways.

What seems to have really increased in last years is the number of feminist and queer political slogans and stencils…

Yes, exactly, things that give a message through to the audience. And I think in general people have become more open-minded about gays, lesbians, queers, they have more rights, so they can be more free and express their opinions. I think generally in Athens, maybe not all over Greece, but in some parts of Greece people are becoming more open-minded. About art, about gender, about everything.

Do you see a connection with the crisis?

Not really. Actually, if there would be a connection, I think it would be the opposite. Because with the crisis the extreme right wing parties have risen, like Golden Dawn, and I think they are not okay with any of these things. They don’t like graffiti and or anything that is different, that they don’t know. They are more close-minded.

Do you consider what you do feminist?

Well, not really, I don’t see it from that perspective, I see it more like art. Because I don’t see myself as different from the others that do graffiti, I feel we are the same, so I cannot say that.

But that is a feminist act, isn’t it? If you assert yourself in a subculture that is predominantly male?

Yeah, well, it could be like that. But it’s not the first thing that I think about when I think about women in graffiti.

There’s definitely a growing recognition for women in street art and graffiti in Athens: there was the “In Broad Daylight” exhibition in NYC and the French “[P]ose ta bombe” documentary, both of which you were featured in. How has that affected you?

I guess more people know about me now, but I still do the same stuff because I’ve been doing this for over 10 years. I’m still doing the same thing, working hard, doing new stuff, looking around.

How did you experience being in the Bronx and connecting with people there?

It was a really great experience, I definitely want to go again next year. We met a lot of people, and the graffiti artists we connected, most of them were between 50 and 70 years old, old school writers. So this gave us strength to go on writing until we die, until the end, until forever.

Did any of the old school female writers come, like Lady Pink?

Yes, Lady Pink came which was really great, knowing another girl that has been writing for about 20 years, so we talked about a lot of stuff. And we realized that actually it’s about the same, whether you are in America, or Europe, or Greece, it’s the same situation, it’s nothing different actually.

And it doesn’t matter if it’s 20 years ago or now?

Yeah, exactly! She told me that she had to do a lot of work to get the recognition… so it’s about the work, not if you’re a girl or a boy.

But you have to work harder when you’re a woman to overcome certain negative expectations, and to be taken seriously so I think it does make a difference.

It makes it a little bit more difficult, especially if you want to do work with it, not just do it as a hobby. You have to work a little bit more I guess, but when years go by and they see you’re still doing it and you love it, I think they accept you at last.

When you go to graffiti festivals, do you often find yourself to be the only woman in the lineup?

Yes! At the festival I went to on Friday, today, and tomorrow, I’m the only one. The one I’m going to next week there’s one more woman. So out of four festivals one has more than one girl.

How do you experience that?

Actually we all know each other from the festivals, so we are friends and I don’t feel awkward or something. We all know each other from different festivals in different areas of Greece so we’re friends, we are connected. It’s a network, not even just in Greece, it’s a global network, and when we go to another city a friend will tell you about another friend that you can find there and so on.

In another interview you were asked about where you like to paint in the city and you said you like to paint in abandoned buildings, can you talk more about that?

Yeah, I like to paint in abandoned buildings. It’s nice to paint in a place with not so many people, because I like going there and not thinking about nothing, just paint. I like painting downtown, too, but I think it’s different, it depends on your psychology.

So when you do paint downtown, do you get any kind of responses when you do it?

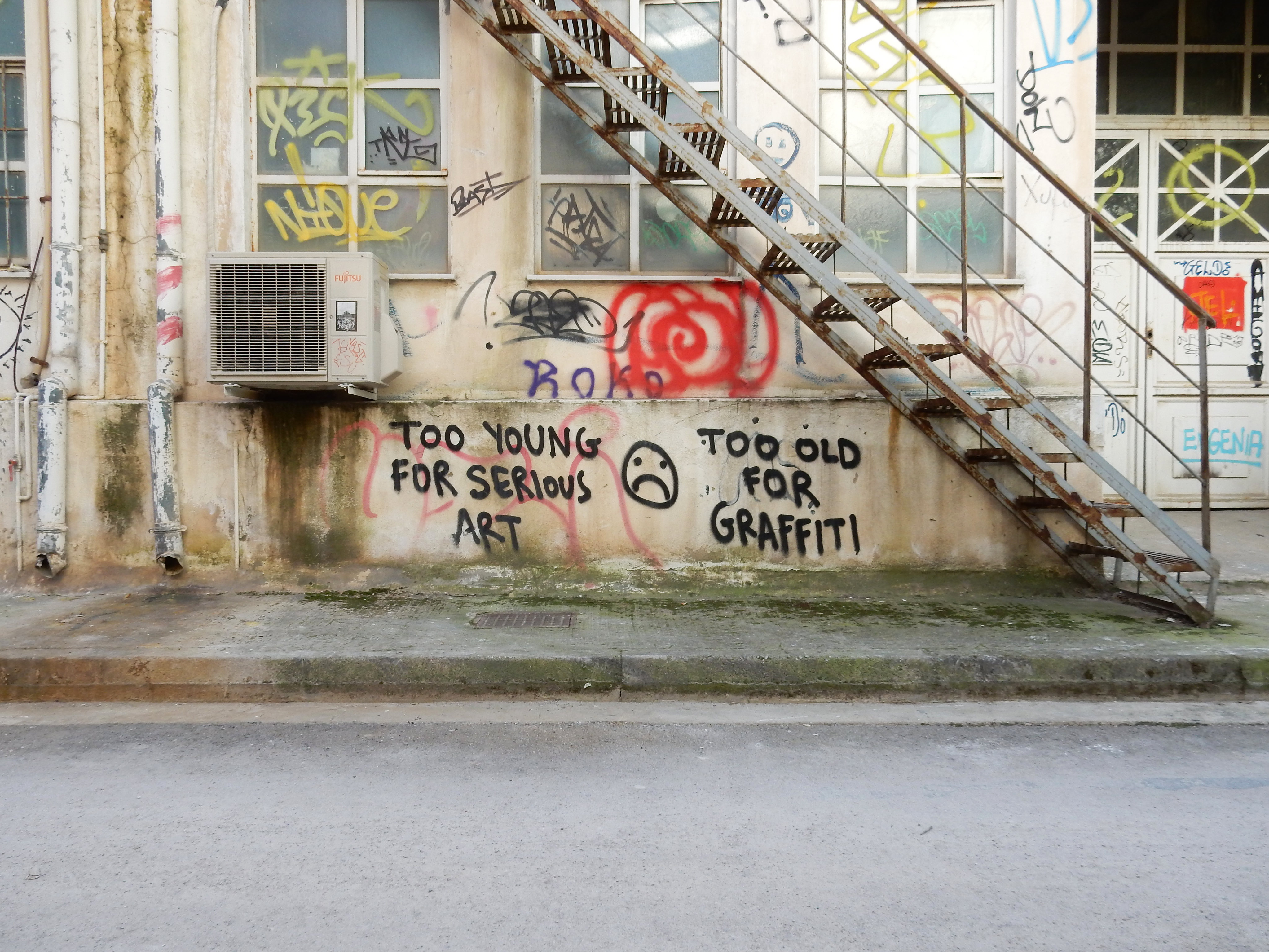

Oh yes, of course. Both good and bad ones. Some of them tell you: wow, very nice piece of work, I like graffiti. Others will come and tell you: that’s garbage, what are you doing, you’re destroying the wall and stuff like that.

Do they ever comment about you being a woman in public space or is it usually about the work?

It’s mainly about the work. Except some teenagers, teenage boys know everything “I can do it better” and stuff. This doesn’t bother me, it happens.

Back to the feminist slogans and stencils we talked about earlier: what do these kinds of messages mean to you, do you have any connections with them?

No, that would be a lie, I don’t really have time for politics. I catch up with politics, I know what’s happening, but when I do graffiti and art it’s not about giving a message to people, it’s just something colorful that makes your day better… Well, it makes my day better and hopefully others.

—

This interview was conducted in person on June 27th, 2018.

Questions and editing by Julia Tulke.