A science slam, in essence, is a format where young scientists and researchers are challenged to present their academic projects in an understandable and entertaining way. The problem: you only have exactly 10 minutes to do so. A few weeks back I was kindly invited by the organizers of Policult to take part in one of their events and ended up on their Potsdam stage in the beginning of February. Here’s the video of my appearance there. As it is only available in German, I provided an English translations below.

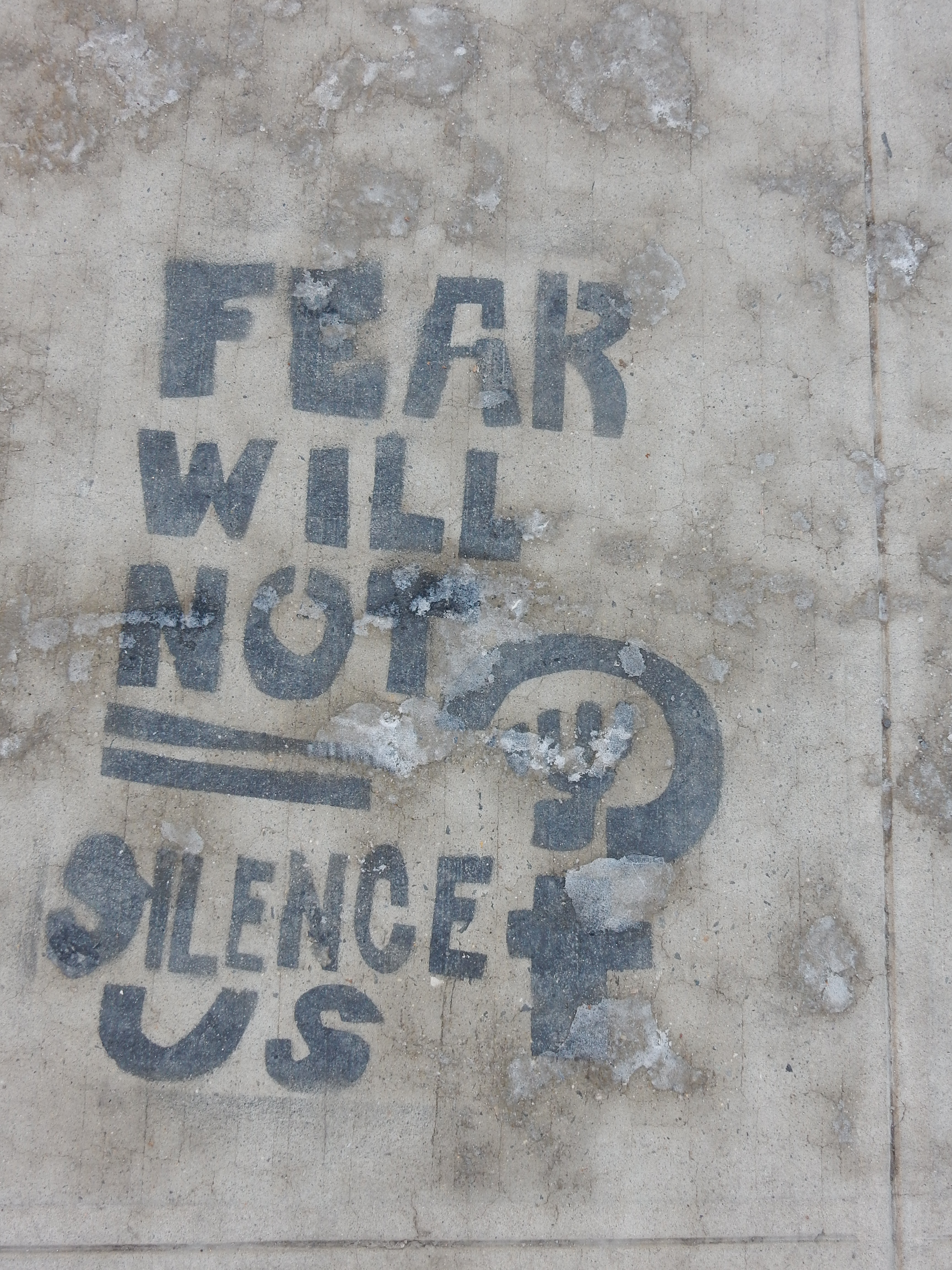

As you can see above, I will talk about street art today, specifically: political street art in Athens in the context of the crisis. As this is an extremely visual topic, I strategically employed a range of visual methods—particulary photography—strategically to approach my field. As an introduction I would like to invite you to let my photographs and words transport you to the crisis city of Athens.

Welcome to Athens.

Symbolic epicenter of the European crisis,

city of conflict,

city of contradictions,

city of decay.

The cradle of democracy stuck in limbo between a present that doesn’t seem to pass and a future that still needs to be designed.

A city marked by 5 years of crisis,

a city full of marked people.

The walls tell their stories, in the cracks of reality,

barely anyone who cares to remove them any longer.

βασανίζομαι (I torture myself),

wake up,

λαθως (wrong),

words cover the streets like tags of the crisis

a struggle over life and death,

projected onto broken and vulnerable bodies,

often of children and young adults,

with hollow cheeks and empty eyes.

fear,

desperation,

hopelessness,

a city in a state of emotional exception.

Welcome to the civilization of fear.

The protest on the walls cannot be evicted.

Gasmasks,

Molotov cocktails,

the city in flames,

everywhere and at all times.

The only terrorist are the 8 o’clock news,

the only terrorist is the state.

And as the fires burn our hearts will unite,

almost a little romantic.

And maybe love will save the world,

but until then—at least in athens—the struggle continues,

ironically,

cynically,

passionately.

But even on the walls of the crisis city there are moments of hope,

new blueprints of society,

geographies of solidarity.

I think we all actually should feel lucky—in quotation marks—because [the crisis] makes us more creative. We are creative now because if we were in a period where everything is calm and nothing really happens we wouldn’t have the motivation to express ourselves. It’s not a good situation to be in, I’m not saying that, but I think it makes you creative. (Refur)

Welcome to athens,

city of creative resistance.

I hope you made it into the crisis with me and I hope this wasn’t too depressing. Despite everything going on, Athens is still a very beautiful and dynamic city where lots of exciting things happen! The one question I face quite often when I tell people about my research is the question how it qualifies as an academic project. After all, street art is a rather universal phenomenon, everybody knows what it looks like, passes it by every day, there are millions of pictures on the internet—so how do you approach it systematically?

First of all i had a clearly defined research question: how do the walls of the city reflect the situation of crisis, which rhetorics and iconographies are mobilized therein and how do they refer to what politics and mass media say and depict about the crisis. It might not bee all that obvious that there is a connection between crisis and street art but there definitely is. First of all the city just lacks capacities and possibly has other priorities that scrubbing graffiti off the walls. As a consequence works stay longer so that there is a possibility for dialogues to develop on the walls. At times artists can also take quite some time to work on an artwork. Secondly, the crisis produces a whole new set of surfaces that are interesting for street artists to engage with: empty shop windows, boarded up doors and windows, abandoned construction sites. And thirdly, as was already made clear in the quotation that I shared earlier, the crisis has generally initiated a creative boost, not only for artists but for activists and regular residents. And of course as a universal reality, the crisis has a strong influence on the contents of the works. As a consequence you can find more street art in Athens, the works are much more political and much more personal. While in Berlin street artists motivation might rather be beautification or putting something fun into urban space, the works in Athens have much more to do with the artist’s everyday realities.

So what did I do, exactly? I conducted a lot of interviews, with artists, activists, and residents and, as I mentioned earlier, started strategically building my own photographic archive. During my time in Athens—3 months at the beginning of 2013—I took more than 1000 pictures of which I selected 850 for analysis. Those 850 photos were geotagged and scientifically coded according to their location, form and technique as well as certain common symbolic elements, such as gas masks or the Euro sign. I eventually identified 3 so-called aesthetics of crisis, ways of representing and dealing with the crisis. The first was direct engagements with the crisis and its institutions—the smallest group with 36 out of 850 photos—the second representations of the crisis as an everyday reality—almost 250—and third political works, such as portraits of activists, protest scenes and political slogans—316 of 850. My codes helped me analyze these photo clusters in a more complex manner. For example I figured out that in artworks directly engaging with the crisis and its institutions, there is an emphasis on standardized symbolic elements like the euro sign or logos of institutions. In works dealing with the crisis as an everyday reality, artistic techniques tend to be much more personal. For example I found a lot of paste-ups, a painting or drawing made on paper and then glued to the wall, suggesting a more personal engagement with public space. Finally, political pieces have a much more meaningful relationship with their respective spatial context. You can find them most densely distributed along classic protest and demonstration routes and in neighborhoods that activists social movements call their homes. Eventually, you can follow those marks and interventions to the significant spaces and places of the crisis.