On March 22, Greece’s conservative prime minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis announced the implementation of an extensive ban on “unnecessary transport and movement of people throughout the country.”1 Cited as the “last step” that “an organized, democratic state” may take in the effort to contain the local spread of the coronavirus pandemic, the measure expanded the friendly social distancing campaign Menoume Spiti [We stay at home], instituted a few weeks prior, into a mandatory, policeable lockdown. As of March 23, mobility in Greece has been constrained to “essential movements,” to be documented via a self-issued permit or text message to an official number, with fines for violations set at 150 euro.2

Since the implementation of the movement ban, Greece’s COVID-19 outbreak has remained relatively contained—cases currently stand at just over 2.200, and deaths at 113—earning the country’s leadership international praise for its successful campaign to “flatten the curve.” After having received little media attention over the past weeks, Greece is now being cited as a best practice example that, as the title of a recent Bloomberg signals, “shows how to handle the crisis.” The underlying narrative is consolidating around a problematic notion of crisis resilience: Greece, whose public health care system was decimated by years of austerity imposed in the wake of the Greek sovereign debt crisis, knew to act swiftly in order to avoid a potential catastrophe. The country’s dysfunctional public health infrastructure—at the beginning of the outbreak there were no more than 530 ICU beds for a population of over 10 million—is here seen less as a cause for critique of the European austerity regime, but rather reframed as the basis for virtuous decision-making.3 Similarly, the Greek people have been described as exceptionally compliant with the lockdown measures, which Alex Patelis, economic adviser to the PM, has attributed to the fact that they “have been through crisis; they know what it is [which has] enabled them to adapt and be stoic.”4

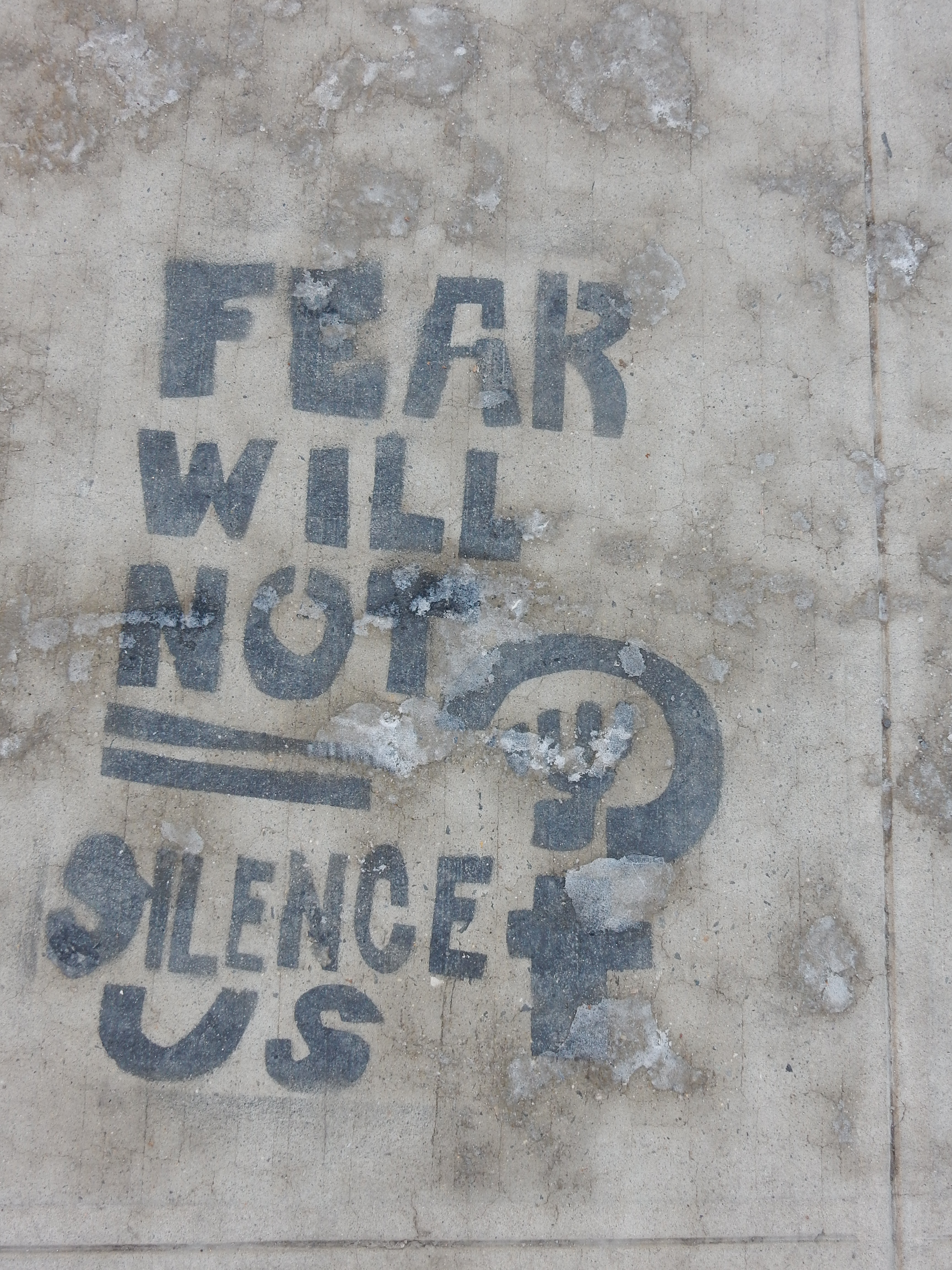

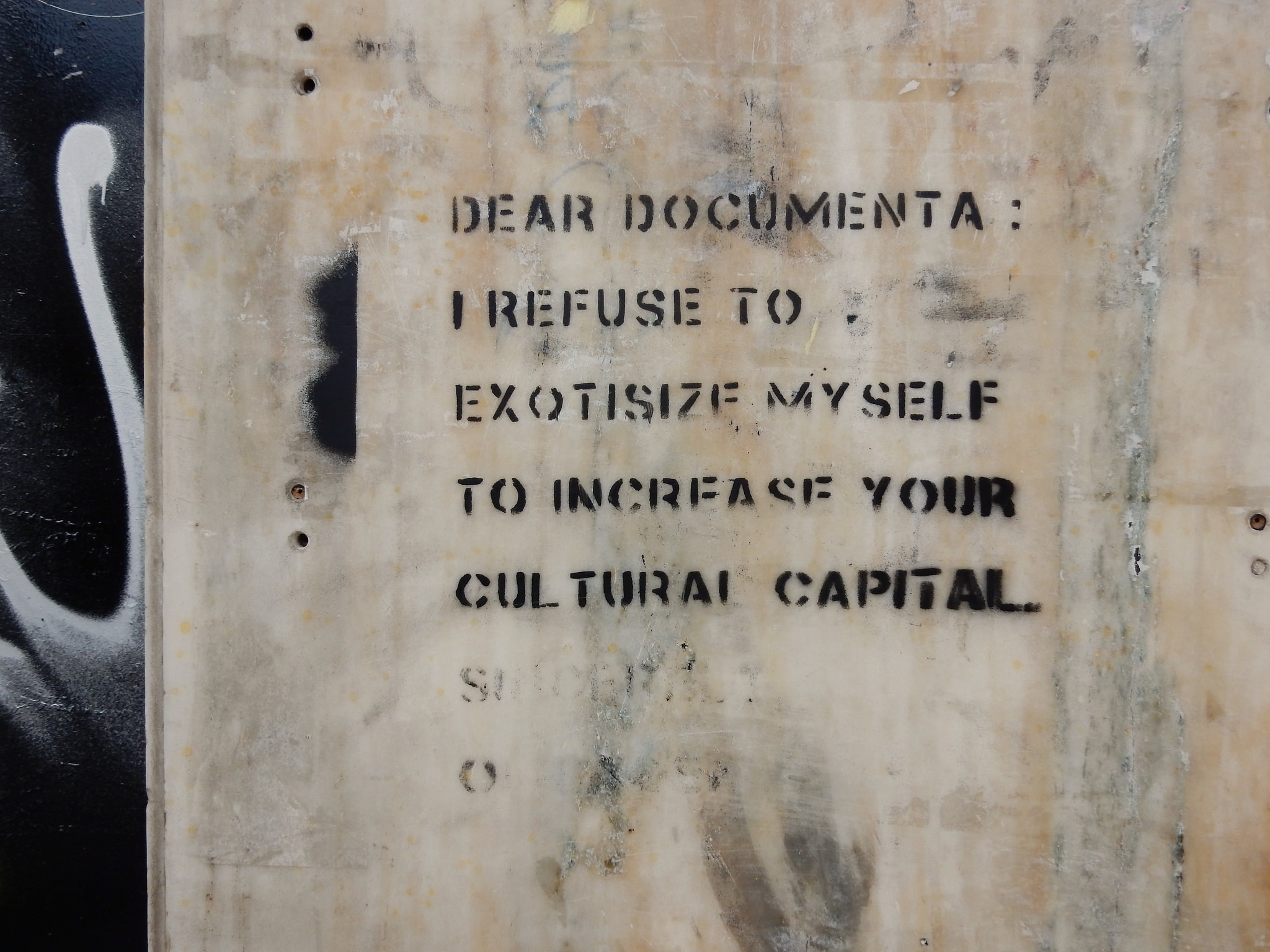

Witnessing the first month of the lockdown from the streets of Athens reveals a more nuanced set of perspectives on the current moment, with stickers, flyers, posters, banners and graffitied slogans, disseminated mainly by leftist activist collectives, offering critical commentary on the social and political implications of Coronavirus governance, understood here as an extension of the biopolitical apparatus of austerity.5 These interventions, which are often removed swiftly, project a deep skepticism about the expansion of government authority in the coronavirus crisis, while also drawing attention to the uneven distribution of vulnerability in the present moment. This emerging archive of public dissent challenges the notion that COVID-19 renders cities empty and lifeless. Rather, as the following examples from one month of lockdown in Athens document, the city’s streets remain a dynamic site of contestation and meaning-making.6

Note: The works presented below can be attributed to at least eleven different political groups, collectives, and organizations that are part of the highly heterogenous composite of political and theoretical viewpoints that is “the Greek left.” Readers are encouraged to engage with these groups and the material they’ve published on the Coronavirus crisis directly in order to better understand the intentions behind the pieces featured in this post: Antifa South, Assembly against Biopower and Confinement, Autonome Antifa, Grammi15, Migada, Open Assembly of Residents Petralona-Thisseio-Koukaki, Socialist Labor Party, Solidarity with Migrants, Steki Antipnoia, SYBXPSA.

Menoume Spiti: The Politics of Staying at Home

As the government has largely centered its mitigation efforts around the Menoume Spiti [We stay at home] campaign, it has failed to adequately address those for whom home is a fraught concept: those who have no home, those for whom staying at home may result in exposure to gender-based violence, and those who are confined under unsafe conditions in prisons and refugee camps. The privilege and politics of staying at home are the central concern of a number of interventions that have emerged during the lockdown.

“It’s not the Flu, It’s an Experiment in Public Order:” Resignifying the Lockdown

In Greece, as elsewhere, the protection of public health (“the lives and health of the Greek people!”) is cited as the central justification for the restructuring of everyday life by means of expansive and restrictive policy measures. According to this rationale, lockdowns, un-democratic as they may seem, are strategically deployed in order to delay an escalation of the pandemic, thus “buying time” needed to prepare health care systems. While Greece has received praise for implementing a lockdown early in its outbreak—especially in comparison with Italy and Spain, where governments were more hesitant—the investments in public health have been minimal. At present, testing remains sparse, shortages in ICU beds, staff, and PPE widespread. This glaring discrepancy between political and health measures, paired with a general skepticism of the conservative government of Kyriakos Mitsotakis, notorious for its law-and-order approach to governance, has prompted a number of slogans that offer interpretations of the lockdown beyond the official public health narrative.

“Lockdown to the System:” Resistance, Protest and Collective Organizing

If, as the pieces above suggest, the Greek left is consolidating around a view of the lockdown as not merely a matter of public health, but rather an occasion for the continued expansion and normalization of austerity and law-and-order governance, this spells an urgent need for resistance, protest, and collective organizing. Street-level dissent in Athens is bifurcated into two modes of expression: refusal, usually in the form of graffitied slogans or stickers, or the voicing of specific political demands, often through DIY posters.

“Solidarity doesn’t go into Quarantine:” Solidarity at a time of Social Distancing

As the paradigm of social distancing is fraying social relations and fragmenting communities, activists, NGOs, and neighborhood groups in Athens have been building towards new models of social solidarity and mutual aid. Instructional flyers, distributed and posted up in neighborhoods, are an important means of announcing such efforts to community members. Meanwhile, graffitied slogans, which can frequently be found on the facades of supermarkets and health centers, sustain a more ambient sense of solidarity: no one alone, everything for everyone, society will win!

References

| 1. | ↑ | “Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis’ Address to the Greek People,” March 22, 2020. |

| 2. | ↑ | See “Lockdown Movement Permit: Instructions for all Individuals,” 2020. |

| 3. | ↑ | A similar argument has been made about Eastern Europe, see Bojan Pancevski and Drew Hinshaw, “Poorer Nations in Europe’s East Could Teach the West a Lesson on Coronavirus,” Wall Street Journal, April 12, 2020. |

| 4. | ↑ | Cited in Helen Smith, “How Greece is beating coronavirus despite a decade of debt,” Guardian, 14 April 2020. |

| 5. | ↑ | see Michele Lancione and AbdouMaliq Simone, “Bio-Austerity and Solidarity in the Covid-19 Space of Emergency – Episode One,” Society and Space, March 19, 2020. |

| 6. | ↑ | All photographs in this post were taken by the author between March 23 and April 20—more examples are archived on Flickr. Check out the Facebook pages Η σιωπή είναι συνενοχή and Kropotkin-19 for an archive of political interventions from other parts of Greece and Athens. |